Passing the Torch

15.

Chicago 2003 Annual Meeting: The Schism

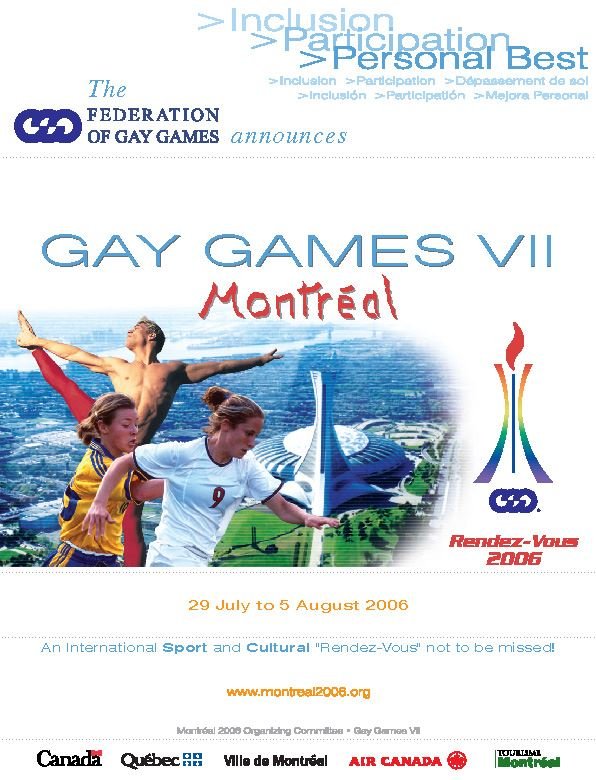

An early flyer promoting the Montreal Gay Games for 2006

KATHLEEN WEBSTER: There were hugs and tears of joy in November 2003 when the negotiating teams for the Federation of Gay Games and Montréal 2006 successfully reached a final contract agreement in Chicago after two years of intense negotiations.

The Federation’s joy of selecting Montréal as the presumptive host for the 2006 Gay Games VII in Johannesburg, South Africa in 2001 and that final success many months later, however, turned to incredulity and disbelief within hours. The Federation board awoke on 9 November 2003 to find that the Montréal team had changed their position and terminated all dialogue. They had left the meeting venue during the night and, at a press conference in Montréal later that day, announced their decision to hold a separate event in 2006.

The Federation board was shocked. On our part, there always had been the desire to find a solution and to establish a partnership to serve our international LGBT sport and cultural community. The Federation had listened to its constituents and taken steps in its 2006 contract to address financial deficits from the four straight hosts of Gay Games III through VI. Yet Montréal 2006 declared that they no longer wanted to work with the Federation – their local business acumen would guarantee their success.

As the board finally accepted the reality of Montréal’s decision not to be our partner, we realized our responsibility remained to work for unity to best serve our global Gay Games community. It was time to acknowledge that our two organizations could co-exist and move forward. It was time to rebuild the Gay Games brand and continue our mission to serve our Gay Games participants and stakeholders by focusing on our statement of purpose: to put on a Gay Games every four years.

As part of rebuilding our brand, we committed to work for understanding and resolution when Montréal’s decision to hold a rival event, after more than 20 years of unity for LGBT athletes and artists, resulted in anger and calls for a solution from our stakeholders. In January 2004, Comité Organisateur-Montréal 2006 issued an invitation for “leaders from various fields related to GLBT sport… to participate” in “Think Tank” meetings in Montréal from 16-18 January to discuss the future of LGBT sports and to “look seriously at some of the issues facing the GLBT sport community in order to ensure everything possible is being done to support its growth.”

The Federation was not invited. Nevertheless, we sent a letter to the organizers requesting that “in the spirit of cooperation, we would like to take this opportunity to participate and work with the meeting attendees toward building a better future for the global LGBT sport community and our supporters from around the world.” The Federation sent two Federation Board officers. The organizers refused to include and permit our representatives to participate.

The Federation continued dialogue with the global sport and arts community and, following the FGG’s open community meeting at its 2004 Annual Meeting in Cologne, Germany agreed to build upon a proposal by Games Berlin and sponsor “an open and inclusive conference aimed toward building bridges within the international LGBT Sport community.” The Federation voted to partner with Out for Sport London as a neutral city with no bid intentions at that time and an accessible location for the majority of our stakeholders. The Federation’s purpose was to be an equal participant at the conference.

After submissions from all attending parties, the Out for Sport organizers hired an independent facilitator to set the agenda and run the meeting. The “Building Bridges for the Future of LGBT Sport” conference took place in London from 12-13 February 2005 and included many LGBT sport organizations and individuals with long histories of service to the international LGBT stakeholders. The new iteration of Montréal 2006, Gay and Lesbian International Sports Association (GLISA), was included and participated.

While the conference did not result in the return to one global event as many had hoped, it did bring about community acceptance that there would be two large events in 2006 and that GLISA intended to continue to promote separate events after their 2006 event, by now called OutGames.

The Federation acknowledged the significant impact this would have on our limited economic, sponsorship, personnel, and venue resources. We also recognized the right of every organization to define and evolve its own mission and our decision was to continue with respectful public statements and our commitment to the Federation’s high standards of professional leadership among our board and strategic partners. The Federation additionally agreed to continue conversations with GLISA to work toward future unity for our community.*

During all this time, with the help of our many supporters, the Federation board continued our work to protect and strengthen our legacy and mission. Two of the Gay Games’ strongest supporters during these times were the cities of Chicago and Los Angeles (both participants in the 2001 bidding process). Each organization worked diligently, gathered tremendous community support, and submitted their bids to step up and host the 2006 Gay Games. After a shortened, thorough and thoughtful bidding process, the board elected Chicago to host Gay Games VII.

Gay Games Chicago logo

The Federation and Chicago’s organizing committee worked assiduously over the following months, each organization committed to continuing the Gay Games legacy. Participants recognized the importance of that legacy and history and over 11,700 athletes and artists and thousands of spectators flocked to Chicago for the week of 16-22 July. The Chicago Gay Games were a resounding triumph.

Critically important, even with significantly less time to prepare than prior hosts, Chicago was the first host since 1986 to end financially solvent, setting the stage for future Gay Games success. Surprising the Federation and the LGBT community everywhere, GLISA’s legacy did not have an auspicious start, as Montréal’s 2006 OutGames resulted in an approximate $5.7 CAD ($4.3 million USD) deficit.

Despite the challenges, the Gay Games happened in 2006 as they have every four years since Gay Games I in 1982. The Federation board is the custodian of the vision and ideals of the founders of this celebration of participation, inclusion and attainment of personal best through sport and culture. The legacy of the Gay Games movement continues and, with the dedication of future Federation boards and the continued support of our community and stakeholders, will prevail for future generations.

*Meetings between the Federation and GLISA continued for the following decade in an attempt to join together for a “One World Event.” I retired from the Federation in 2007 so was not part of these negotiations. I had the honor of serving as a consultant to the Federation Working Group toward the end of their discussions and prior to the Federation’s decision to end further negotiations in March 2016 as no agreement had been reached. GLISA dissolved shortly thereafter.

EMY RITT: [FULL DISCLOSURE: The Author joined the FGG Board in December 2002.]

Although Montreal had been announced in 2001 as the Host of the 2006 Gay Games, ongoing contractual issues had still not been resolved after several years of negotiations and were heading towards a very serious and troubling situation. As the weeks and months of negotiations dragged on, the discussions became increasingly acrimonious and destructive, tearing apart the LGBT+ sports community.

Several lessons were learned from this experience, one being the necessity of establishing a time limit for signing the contract and to have an official “runner-up” organization that would be offered the role of Host in the event of any issues with the initial presumptive Host.

When the schism finally occurred in 2004, FGG re-opened the bidding for the 2006 Gay Games with the three runner-up bidders from the first 2006 Site Selection process: Atlanta, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Atlanta had finished second in the first Site Selection vote, but at that time, the number of votes cast were not taken into consideration in the event of any issues with the presumptive host. Otherwise, Atlanta might have been automatically invited to become the 2006 Presumptive Host.

When the FGG decided, instead, to have a ‘fast-tracked’ Site Selection schedule that included having FGG members vote again, Atlanta, unfortunately, decided to withdraw from the process, leaving Chicago and Los Angeles to go head-to-head. Chicago and Los Angeles saved the Gay Games by agreeing to participate in the second 2006 Site Selection process. In the end, Chicago was selected to be the Host of GGVII, and the rest, as they say, was history. Thankfully, Team Los Angeles has remained very committed and engaged with the Gay Games.

ROGER BRIGHAM: After failing in my attempt to be part of Gay Games I in 1982 and then being prevented from the next five Gay Games because of various personal issues, most especially my combat with AIDS, I became involved in the Gay Games Movement in 2003 when I started to compete in wrestling with Golden Gate Wrestling Club in San Francisco. I had double hip replacement surgery late in 2001 and spent the next two years rebuilding my hip and core strength.

I represented Wrestlers WithOut Borders at the FGG annual meeting in November 2003 in Chicago. I had been given years of the correspondence between FGG and the Montreal bidders by my WWB predecessor, Erich Richter, with the instructions: Read everything and then don’t let anybody tell you how to vote.

I spent several weeks reading all of the documents. I started out assuming the FGG was being picky, and looking forward to winning gold in Montreal while getting married th.ere. But the correspondence compelled me to conclude that Montreal had been stalling throughout negotiations, repeatedly conceding on issues and then reneging on the agreements later, with the full realization that FGG had no backup plan, no alternative host identified, and would wind up with virtually no choice but to concede on every issue and lose all control over the event.

I said nothing the first few hours of the initial session of the annual meeting. We were warned of crippling lawsuits if we failed to agree to Montreal’s final terms, which would surrender the oversights that held hosts accountable to FGG stakeholders. I heard a lot of vitriol and drama. I heard lots of sky-is-falling prognostications. I finally heard enough.

During lunch I sought out a lot of the delegates, many of them also in their first FGG meeting, and told them the correspondence of the previous two years had convinced me the FGG and Montreal were in a dysfunctional, abusive relationship and the worst thing that could happen would be for them to be locked together in a marriage for the next three years. I spoke in the afternoon session and reminded my fellow board members that we were athletes, and you learn as an athlete to fight as a team for what you know is right.

Montreal negotiators had already walked out the door, telling us to accept their terms or they would go on with their event without us. By the margin of a single vote, we let them walk and prepared to carry on the Gay Games without them.

LAURA MOORE: I had been very excited when Montreal won the bid. We had a number of Canadian figure skaters and had had gay skating events there already. What the press called a “Schism” was, to many of us, an attempted hostile takeover. When Montreal walked away from the contract negotiations and announced plans to hold a competing event, I was shocked. Even more dismaying was the fact that some of my friends and colleagues were abandoning the Gay Games and jumping on board.

I am still grateful that Chicago came to the rescue and put on a hugely successful Gay Games with only two years lead time, but the confusion among our constituents and the temporary damage to the Gay Games brand were significant. The Gay Games and The OutGames were held only days apart. Some chose the Gay Games out of loyalty, but where Montreal offered sports not available in Chicago, participants had their choice made for them.

IGFSU ran the figure skating competition at the first OutGames, not out of support for GLISA but to insure that figure skaters were protected with appropriate ISI endorsements.

The GLISA logo

That GLISA and the OutGames came to an end after a few tumultuous years is testament to the long-term viability of the FGG and the Gay Games.

SHAMEY CRAMER: Following Gay Games VI: Sydney 2002, Los Angeles decided to put together an exploratory committee to see about bidding for Gay Games VIII in 2010. However, things did not seem to be going well with the FGG and their negotiations with Montreal.

In March 2003, the Gay and Lesbian Athletic Foundation hosted a conference at MIT in Boston. Six FGG Board members hosted a panel discussion, and I was on the panel for HIV & Athletics. Representatives from the Montreal bid team were there as well.

Following the FGG presentation, the two Montreal representatives took me aside and complained about the negotiations with the FGG. At one point, they said: “the FGG needs to go; would you be willing to work with us to replace them with a better organization?” I informed them that although I had my own differences with the FGG, I was someone who always felt it best to try and create change by working within the organization.

Fast forward eight months to the FGG’s Annual Meeting, which was held in Chicago. The meetings began on 10 November. During the third day, we were informed that Montreal had pulled out of negotiations and had already left town. Given their comments in March, and their actions in Chicago, it seemed that they were also trying to do to the Gay Games what the USOC attempted to do – cripple them financially to the point of extinction.

The next morning, the FGG Site Selection Committee met with representatives from Atlanta, Los Angeles, and Chicago – the three finalists in Johannesburg two years earlier. Since Atlanta had the most votes of the other three finalists, they felt they should be given the right to enter negotiations with the FGG. But the FGG didn’t see it that way, and decided to have a second, abbreviated bid process. Atlanta chose not to rebid, and Chicago wasn’t so sure. As one of the Chicago bid members said to me during Site Selection meeting break: “Los Angeles may get these by default.” The FGG gave us until 15 December to submit a Letter of Intent.

As soon as I got back to Los Angeles, we got Los Angeles Mayor James Hahn to submit the letter, and the City Council once again voted to create a Gay Games Task Force, appointing me as its Chair, with representatives from more than a dozen city departments and agencies, as well as representatives from each of the fifteen council districts.

The morning of December 15, I got a call from the FGG. They asked if we would mind if they extended the submission date for another week, since Chicago was still undecided. Although our Task Force was a bit put off by the FGG asking a bidder how they should run their process, we agreed to the extension, not wanting to seem difficult.

A week later, the FGG called again, asking if it was OK to once again extend the submission deadline another week, in order to appease Chicago. At this point, many on our committee were irate that the FGG would put our committee into the position of doing their work for them, but we again agreed to give them an extension.

When Chicago was selected two months later, our Task Force representative from the City Attorney’s office explored the option of suing the FGG for their poor handling of the process, but decided against it. To add insult to injury, FGG Co-President Roberto Mantaci called me after the vote, saying they had to give the two extensions because it wouldn’t have looked right to have a bid process with only one bidder.

Although I still loved the concept of the Gay Games, and what they stood for, I was not at all happy with how the event was being managed, and vowed to join the FGG at some point to make sure no other bidders had to go through the hell we were put through as a result of their lack of professionalism.

In April 2004, one of the Montreal representatives with whom I had interacted in Boston was in Los Angeles seeking media sponsorships. When we met, he asked if I would be willing to work with them to “destroy the FGG” (his actual words) and replace them with their new organization and event. They even offered to let Los Angeles host OutGames II, three years after the inaugural Montreal OutGames in 2006.

I told them that as unhappy as I was with the FGG for how they conducted their business, I would have to think about their offer. But there was no way I would ever be interested in dismantling the Gay Games.

ROGER BRIGHAM: After the 2003 FGG meeting in which Montreal walked, members of the Executive Committee waived the usual requirements and asked me to serve on two special committees: the Strategic Planning Committee, as one of the co-chairs; and the Host Advisory Board. The SPC was tasked to address many of the structural and cultural shortcomings of the organization; HAB would negotiate license terms with new presumptive host Chicago and interact with the host organization moving forward.

An immediate task was placed before me: attend the 2004 Gay and Lesbian Athletic Foundation meeting in Boston as a witness, than prepare an analytic report on the presentations of Chicago, the FGG, Montreal, and the newly formed Gay and Lesbian International Sports Association.

During breaks between sessions at the GLAF meeting, I observed several Montreal/GLISA representatives buttonholing sports representatives to press the Outgames cause. Rumor had it that an announcement would be made the next day that a second Outgames would be held in four years. There was a lot of pushback. I heard one sports leader shouting at a GLISA rep, “If you say you’re going to hold another Outgames in four years, everyone will know you are out to destroy the Gay Games!”

The next day it was announced a second Outgames would be held in three years, not four.

There was a good bit of time left over at the end of each breakout session. At the end of those sessions, sports club representatives informally asked a lot of questions about practical issues their clubs faced — things such as membership, marketing, insurance, and venues. I noted that the FGG and Chicago representatives always stayed and offered advice about solutions they had used. The GLISA and Montreal representatives never stayed, never offered advice.

Montreal bragged in its budget presentation that it had already raised $3 million, which impressed the hell out of everyone in the room. In the Q&A session that followed, it was revealed that the $3 million was already consumed with commitments — none of them having to do with the actual sports competitions.

I reported to the FGG Executive Committee that the Montreal Outgames would never be held — or if they were held, they would be a financial disaster. It was not being run by sports people and its work was not focused on sports. Less than three years later, that prediction proved to be disastrously true.